A new CGFS paper suggests that bank regulatory capital and liquidity changes may [i] reduce liquidity in money markets, [ii] create steeper short-term yield curves, [iii] weaken bank arbitrage activity, and [iv] increase reliance on central bank intermediation. Profit opportunities may arise for non-banks.

Committee on the Global Financial System, Markets Committee (2015), “Regulatory change and monetary policy”, CGFS Papers No 54, May 2015

http://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs54.pdf

On the broader systemic consequences of regulatory tightening view post here and here.

The below are excerpts from the paper. Headings and cursive text have been added.

A quick review of key regulatory reforms

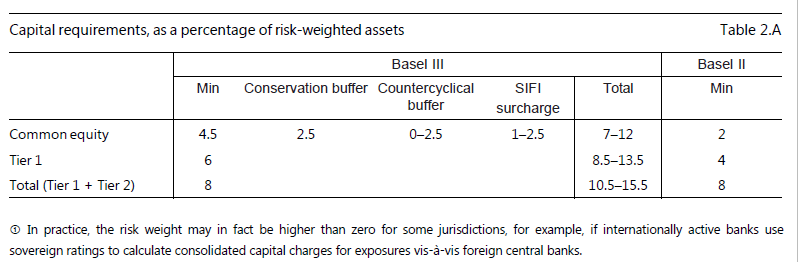

Basel III risk-based capital regulation: “A number of new elements…boost banks’ capital base. First, [the risk-weighted asset measure] incorporates a significant expansion in risk coverage, which increases risk-weighted assets…specifically…trading book exposures, counterparty credit risk and securitized assets. This builds on the earlier approach under Basel II, which introduced differentiated…risk weights (which are either internal model-based or set by regulation). Second, and critically, Basel III tightens the definition of eligible capital, with a strong focus on common equity. This represents a move away from complex hybrid capital instruments that proved incapable of absorbing losses in periods of stress.

A unique feature of Basel III is the introduction of capital buffers…First, a conservation buffer is designed to help preserve a bank as a going concern by restricting discretionary distributions (such as dividends and bonus payments) when the bank’s capital ratio deteriorates. Second, a countercyclical buffer – capital that accumulates in good times and that can be drawn down in periods of stress – will help protect banks against risks that evolve over the financial cycle. Finally, a capital surcharge will be applied to global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), or banks with large, highly interconnected and complex operations.”

Leverage ratio: “The Basel III minimum leverage ratio is intended to restrict the build-up of leverage in the banking sector, and to backstop the risk-based capital requirements with a simple, non-risk-based measure…The LR is defined as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to total exposures. The denominator consists of the sum of all on-balance sheet exposures, derivative positions, securities financing transactions and off-balance sheet items. As such, the total exposure measure includes central bank reserves and repo positions.

Public disclosure of the regulatory LR by banks commenced on 1 January 2015. The final calibration and any further adjustments to the definition will be completed by 2017 with a view to migrating to a binding Pillar 1 requirement on 1 January 2018.”

On other unintended consequences of the leverage ratio requirement view post here.

Liquidity Coverage Ratio: “The stated objective of the LCR is to ensure that banks maintain an adequate level of unencumbered, high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) that can be converted into cash to meet their liquidity needs under a 30-day scenario of severe funding stress. It is defined as the ratio of the stock of HQLA (numerator) to net cash outflows expected over the stress period (denominator)…

The HQLA definition groups eligible assets into two discrete categories (Level 1 and Level 2). Level 1 assets, which can be included without limit, are those with 0% risk weights for Basel II capital calculations, such as cash, central bank reserves and sovereign debt (which may be subject to haircuts). Level 2 assets, which can make up no more than 40% of the buffer, include assets with low capital risk weights as well as highly rated non-financial corporate and covered bonds, subject to a 15% haircut…

The initial minimum requirement of 60%, effective January 2015, will be increased in a stepwise fashion to 100% by 2019.”

On the liquidity coverage ratio’s effect on monetary policy and the term premium also view post here.

Net Stable Funding Ratio: “The aim…is to limit overreliance on short-term wholesale funding… The NSFR is defined as the ratio of available stable funding (ASF) to required stable funding (RSF), which needs to be equal to at least 100% on an ongoing basis.

The numerator is determined by applying ASF factors to a bank’s liability positions, with higher factors assigned for longer maturities (according to pre-defined buckets: less than six months, between six and 12 months, and higher), and more stable funding sources. The denominator reflects the product of RSF factors and the bank’s assets, differentiated according to HQLA/non-HQLA definitions and by counterparty (financial/non-financial). Asset encumbrance [pledging or earmarking for secured liabilities] generally results in higher RSF factors…

The…NSFR, will be introduced as of January 2018.”

For more insights into the net stable funding ratio view post here.

Large exposure limits: “The large exposures (LE) framework of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) is a set of rules for internationally active banks aimed at reducing system-wide contagion risk. It imposes limits on banks’ exposures to single counterparties…

Under the LE framework, a bank’s exposure to any single counterparty or group of connected counterparties cannot exceed 25% of the bank’s Tier 1 capital. A tighter limit of 15% is set for exposures between banks that have been designated as globally systemically important…Exposures to sovereigns and central banks…are exempt from the limit….

The framework is due to be fully implemented on 1 January 2019.”

Less liquid and more volatile money markets

“Activity in short-term unsecured markets is likely to contract. Lower volumes would be driven primarily by the leverage ratio (which tends to discourage money market borrowing) and the incentives set by the liquidity coverage ratio (which reduce demand for, and increase supply of, short-term money).”

“The implied capital requirement of the leverage ratio tends to increase the cost of banks’ repo and similar secured transactions relative to other activities and may reduce their incentives to conduct money market arbitrage and provide market-making…Money market volumes should decrease, with market composition moving towards relatively less repo borrowing…The impact of the leverage ratio on money markets works through both the demand for and the supply of cash balances. Borrowing via repos and other secured transactions will tend to become more expensive, as the leverage ratio effectively ‘taxes’ transactions that expand the balance sheet.”

“The leverage ratio may also lead to increased rate volatility, for two reasons. First, given that activity levels are expected to fall, liquidity is also likely to be lower, which will tend to push up bid-ask spreads. Second, if banks seek to economise on the amount of central bank reserves that they are willing to hold at given levels of interest rates, then smaller reserve buffers may leave them needing to bid up for cash in short-term money markets in response to unexpected shocks, increasing market volatility.”

Yield curve effects

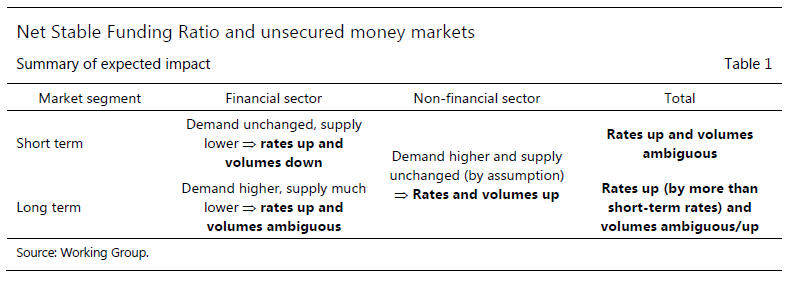

“The [liquidity coverage ratio] encourages banks to term out their unsecured wholesale funding because longer-term funding (> 30 days) does not impact net cash outflows. As a result, the demand for longer-term unsecured funding will rise and, indirectly, that for short-term unsecured funding (< 30 days) will fall. In a similar way, the liquidity coverage ratio incentivizes banks to shorten the maturity profile of their wholesale lending, implying supply shifts that are in the opposite direction to the demand shifts….The net effect of these shifts in demand and supply implies a steepening of the short end of the unsecured yield curve, as longer-term rates rise and shorter-term rates fall.”

“The provision of unsecured funding out of existing cash balances reduces the net stable funding ratio, which is defined as the ratio of available stable (ASF) to required stable funding (RSF), regardless of duration or type of counterparty. This is because the RSF factor (weight) for loans is greater than the RSF factor on cash and claims on central banks. The RSF factor applied on unsecured loans increases with the duration of the transaction. In sum, supply of unsecured lending may fall – particularly at longer tenors and if banks rely on short-term wholesale funding from other financial institutions to finance such lending.”

“In the longer-term interbank market, in contrast, the net stable funding ratio does increase demand (as the ASF factor on these longer-term bank liabilities is positive)…The larger reduction in supply at longer tenors exacerbates this move in rates, such that the short end of the yield curve will tend to steepen.”

Reduced arbitrage in financial markets

“New regulations, such as the leverage ratio, may disincentivise certain low-margin arbitrage activities, such as banks’ matched repo book business… This reduction would tend to weaken, and make more uncertain, the links between policy rates and other interest rates, weakening the transmission of monetary policy impulses along the yield curve as well as to other asset prices relevant for economic activity.”

“The net stable funding ratio (NSFR) is likely to have a particular impact on certain types of repo market making, which will in turn tend to reduce volumes – implying an expected net reduction of money market volumes. This is because, for perfectly offsetting standalone transactions, the negative NSFR impact of a reverse repo exceeds the positive NSFR impact of a repo. The same applies for short-term matched-book activity between two financial counterparties.”

Increased central bank intermediation

“Weakened incentives for arbitrage activity and greater difficulty predicting the level of reserve balances may lead central banks to broaden the scope of their operations (e.g. by interacting with a wider set of counterparties or in a wider set of financial markets) to achieve their policy objectives.”

“In a number of instances, the regulations treat financial interactions with the central bank more favourably than interactions with private counterparties. For example, in the LCR, the rollover rate on a maturing loan from a central bank is 100%, whereas the maturing of an otherwise identical loan from a private counterparty could be as low as zero, depending on the collateral provided. Similarly, large exposure limits do not apply to the central bank, but may limit interaction between larger private counterparties.”